2006: a space oddity – the great Pluto debate

Long known as the ninth planet, Pluto was downgraded in 2006, sparking a scientific spat that raises basic questions about how we understand the universe

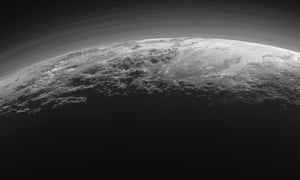

Ninth rock from the sun: when Pluto lost its official status as a planet, it set scientists Alan Stern and Mike Brown on an interplanetary collision course. Photograph: AP

Andrew Anthony Sunday 1 May 2016 09.00 BST

Imagine that you have nurtured an ambition for 25 years to head up an expedition to the last unexplored planet in the solar system. You’ve worked your way up and through countless other suborbital, orbital and planetary missions. You’ve written scores of scientific papers. Finally, you are the principal investigator on Nasa’s New Horizons mission to Pluto – that mysterious little entity, a third of the size of our moon, that is located, depending on orbital position, between 2.6bn and 4.7bn miles from Earth.

In January 2006, your probe leaves Earth on its nine-year journey to its historic destination. It is the crowning moment of your career, a landmark project; you’ve reached the peak of your profession. Then, seven months later, with your spacecraft still in the early stages of its odyssey, it is announced, following a vote at a meeting of the International Astronomy Union (IAU) in Prague, that Pluto is no longer a planet.

As the consequence of the findings of an ambitious planetary astronomer, the elite group of nine planets has overnight shrunk to eight, and your mission is now heading towards a “dwarf planet”, just another piece of ice and rock in the vast Kuiper belt, the band of mostly small bodies that forms the perimeter, the unglamorous outer suburbs, of the solar system. That’s exactly what happened to Alan Stern a decade ago.

Shift forward nine years, and New Horizons has just stunned the world with the clarity and drama of the images of Pluto sent back from its flyby. Hundreds of millions of people go online to look at them. Stern is the subject of international attention, feted, apparently vindicated, a man who appears to have answered his critics about the relevance of Pluto.

But then, out of the blue, the same astronomer whose original research prompted the demotion of Pluto announces that he’s discovered evidence of Planet Nine, a major planet somewhere between the size of Earth and Neptune, that could take the place of Pluto – the original ninth planet – in the known planetary system. That is exactly what Mike Brown did.

Planetary science is a competitive field that, like any area of learning, can throw up bitter rivalries, but the stellar careers of Stern and Brown seem to be plotted along some kind of interplanetary collision course. When Brown made his announcement about Planet Nine, Stern tweeted: “Hype. There is no discovery.” To say there is no love lost between the two scientists would be an exercise in colourless understatement.

But their dispute is more than a clash of personalities, or even professional one-upmanship. It is about the nature of reality, how we make sense of the universe, the things in heaven and earth that are dreamt of in our philosophy.

Stern is a small man with a big office, located in the Southwest Research Institutein Boulder, Colorado. A neatly groomed, 58-year-old ball of energy, he is an aerospace engineer, trained pilot and very proud and angry Pluto advocate.

Stern is proud because New Horizons, which is continuing its journey beyond Pluto into the furthest reaches of the Kuiper belt, has been a huge success and will almost certainly transform our understanding of our cosmic surroundings. He is angry because he believes Pluto has been the victim of a personal vendetta and a shady conspiracy.

Stern rejects the IAU vote that demoted Pluto to the status of dwarf planet.

“Science isn’t about voting,” he says. “We don’t vote on the theory of relativity. We don’t vote on evolution. The image of scientists voting gives the public the impression that science is arbitrary.”

As far as he is concerned, the vote was the final stage of a campaign to discredit Clyde Tombaugh, the son of Kansas farmers who, as a 24-year-old researcher, discovered Pluto in 1930.

“There was an astronomer named Brian Marsden who for decades had a grudge against Tombaugh. He had public fights that many people observed. Tombaugh died in 1997 and Marsden went on a jihad to diminish his reputation by removing Pluto from the list of planets. He eventually found a way to do that at a convention of astronomers, a meeting with thousands of people, of which a very small fraction – 4% – went to a room where the vote was taken.”

Marsden, who was director of the IAU’s Minor Planet Center in 2006, is himself dead, and it is impossible to prove or disprove Stern’s allegations. But 10 years on, the decision taken that day still rankles with Stern. It annoys him that the science press didn’t question the process. But what really gets to him is that the people who voted were astronomers and not, by and large, planetary scientists. He argues that they had little or no expertise in the field.

“Just as you shouldn’t go to a paediatrist for brain surgery, you shouldn’t go to an astronomer for expert advice on planetary science. My field is called planetary science. It involves the word planet in the name. As planetary scientists we should be able to understand what is and isn’t the central object of the field. It isn’t called ‘things in space’. It’s called planetary science. Its about planets.”

Essentially, the IAU laid down three criteria for planetary status. The object has to be in orbit around the sun. It must have sufficient mass to assume hydrostatic equilibrium, meaning it must be spherical by force of its own gravity. And it must have “cleared the neighbourhood” around its orbit, which is to say that it must be gravitationally dominant over surrounding objects. Pluto, the elliptical orbit of which is affected by Neptune’s gravity, fails this test.

Stern dismisses this criterion as too vague, arguing that it means Neptune shouldn’t qualify as a planet. “If Neptune had cleared its zone,” he has said, “Pluto wouldn’t be there.”

“Mike Brown and some other people who for some reason would like to manage the number of planets to be small use a location-based definition, which is about what has cleared its zone. But it’s a very poor scientific concept. I’ll tell you why.”

He says the criterion means the physical properties of a given object are rendered meaningless because location determines classification. “If you accept at face value the zone clearing criteria, you can write down an equation for it. That equation depends upon several things, including the mass of the star it is orbiting, its distance from the star and how old it is. The most sensitive parameter is distance. As you go outward, the clearance zone gets bigger. And as you go outward the orbit speeds get progressively slower. So it takes a more and more massive object to clear the zone as you move farther out. Which means that objects that classify as planets close to a star cannot classify as a planet far from a star.”

Stern says that if Earth was located in Pluto’s position in the solar system it also wouldn’t qualify as a planet. “It’s ridiculous,” he says. He even claims that, according to the maths, Brown’s Planet Nine would not quality for planetary status, “no matter how massive it is”.

Brown’s response is dismissive. “Earth in the Kuiper belt? That would be fascinating, but there is no Earth in the Kuiper belt. Why not? Probably because the formation of the solar system has prevented such a thing from happening.

“The solar system is so cleanly sorted into gravitationally dominant things (planets) and the tiny things that flit around between them (not planets), that that is telling us something truly interesting about the formation of the solar system.”

As for the notion that Planet Nine is disqualified from planetary status by the same criterion that disqualified Pluto, Brown says: “This is, of course, not true – and I’m pretty sure Alan knows this. There is an elegant set of calculations by Jean-Luc Margot which attempts to put real math behind the vague ‘cleared out the orbits’ language. Planet Nine easily fulfils Margot’s mathematical constraints.”

Yet the question remains, if the formation of the solar system prevented an Earth-size planet from being in the Kuiper belt, why didn’t it prevent the still larger Planet Nine? The most likely theory is that, if it does exist, Planet Nine began its orbital life much closer to the sun and then crossed paths with a planet like Jupiter, which sent it spiralling into the outer reaches.

Two more different characters than Stern and Brown it would be hard to conceive. When I visited Boulder, snow was on the ground, and there was something coiled and defensive about Stern, as if he were used to fighting for scare resources in a harsh environment.

Brown is professor of planetary astronomy at the California Institute of Technology (Caltech) in Pasadena, California. In Pasadena, the sun shone and the temperature was in the high 70s.

Brown is Stern’s junior by eight years, but they seem not just a generation but a whole culture apart. Brown was wearing shorts, Birkenstocks and a goatee beard when I visited his light-filled office on the Caltech campus. If the choice of epithets for the two men came down to “uptight” and “laid back”, it wouldn’t be hard to assign them.

Ever since Tombaugh first discovered it, Pluto has held an uncertain position in planetary science. Initially it was thought to be roughly the mass of the Earth, owing to its presumed gravitational effect on Neptune and Uranus. But over the years that estimate was downgraded until now it is thought to be about one five-hundredth of the Earth’s mass.

In 2005, Brown discovered an object in the Kuiper belt that had greater mass than Pluto. This new body, called Eris, presented a classification problem. Either it was a 10th planet or, if it was not a planet, then neither was Pluto. Although he had always dreamed of finding a planet, Brown was inclined to the latter opinion.

“Pluto,” as he tells me, “is essentially this insignificant chunk of ice that really is of no consequence in the solar system.”

He felt pleased when its planetary status was removed.

“It was immensely satisfying to have the solar system described correctly for the first time. It’s painful every time I see something that gives the wrong impression of reality.”

But a lot of people were sentimentally attached to the idea of Pluto and took against Brown’s position. He wrote an entertaining and enlightening memoir about the experience of becoming a hate figure, entitled How I Killed Pluto and Why It Had It Coming.

Stern believes the book has undermined Brown’s objectivity. Interestingly, both Stern and Brown challenge each other’s opinions on similar grounds. Both think the other is compromised by personal involvement, and each believes the other is responding irrationally owing to emotional reasons.

“Mike’s written a very successful book,” Stern told me, “so he’s made a lot of money out of this. I don’t get paid more or less depending on what I say, but he clearly does. So there’s a bit of a conflict of interest. He’s never going to change his mind because it will kill his book’s sales.”

I checked Brown’s Amazon bestseller position. His book was at 131,246 on the list – not a ranking likely to represent large or profitable sales.

For his part, Brown says of Stern: “We should discount him. He’s got a spacecraft that flew by Pluto. You kind of fall in love with the things you spend a spacecraft to. It matters to him personally that it’s a planet. So ignore him.”

The two men accuse each other of suffering from nostalgia for a bygone age of certainties. In Stern’s case, Brown says he wants a return to a time when Pluto was part of the canon, one of the dominant objects. Stern argues that, on the contrary, he believes in a whole new paradigm in which the solar system contains many planets – probably, be says, about 1,000. And it is Brown, he says, who is holding on to a vanishing past of few planets for fear that “schoolchildren won’t be able to remember their names”.

Stern reaches for a geographical analogy. “We don’t limit the number of mountains or rivers of the Earth,” he says.

Brown counters with his own bit of geography. “It think it’s important to us that there aren’t that many planets. I think the word planet is like the word continent. There needs to be a smallish number of them. If every island was a continent, it wouldn’t mean anything.”

Ultimately, he concedes, it comes down to what we want to believe. He says he asked a philosopher friend what does a word – like planet, for example – mean.

“He said the word ‘planet’ means what people think about when they say the word ‘planet’, and I was like, ‘Shut up!’ But then I realised it’s true. And the word ‘planet’ means, in our heads, a small number of large bodies in the solar system. I don’t think it means everything round. It doesn’t mean everything that goes round the sun.”

The official designation for Pluto, Eris, and several other objects found in the Kuiper Belt is dwarf planet. But of course, in an obvious sense, whatever we call Pluto doesn’t change what it is. And what it is, according to Stern, is something of a surprise.

“Number one surprise,” he says, “is that Pluto is so complex. If you plot the numbers of different kinds of geology we see on the surface, it rivals Earth and Mars. Generally, the smaller objects are simpler. Pluto is completely anomalous in that respect. And we didn’t expect Pluto to be active geologically, four and half billion years after its birth. The heart-shaped region we call Sputnik Planum is a million square kilometres. It is the scale of the state of Texas and it was born yesterday. We can’t find a single crater on it.”

To say that Pluto is an insignificant chunk of ice and rock may be true in the grand scheme of things, but meaning is not immanent in any planet or dwarf planet: it comprises what we impose on it. And Pluto is part of our history, a touchstone in our scientific journey outwards.

There is probably no definition of the word planet that suits everyone. By Brown’s understanding a planet can cease to be a planet if, for whatever reason, it changes location, while by Stern’s reckoning the moon is a planet. As Brown says: “Does any scientist anywhere other than Stern think that the moon should be called a planet? I think this is the strongest argument against a geophysical definition.”

The latest research suggests that Brown’s speculations about the existence of Planet Nine, based on the strange alignment of other bodies, may well be correct. If Pluto is ruled out, there have been only two planets discovered, other than by the naked eye, in human history: Uranus in 1781 and Neptune in 1846. So it would be a rare achievement to uncover a third. Brown says it is hard not to be aware of the historical significance. But Stern is having none of it.

“It’s not the ninth planet, right. I think it’s a really insensitive terminology because it trashes Tombaugh’s reputation. Either that or he’s clueless. I don’t know, ask him.”

I did.

“I think that’s a desperate stretch,” says Brown.

And so it goes on, the two esteemed planetary scientists, circling one another like two great bodies struggling for gravitational superiority, both hoping to see the other’s argument propelled out into the forgotten depths of oblivion. And all because of a disagreement about a tiny rock more than 3bn miles away. That, and the unending search for cosmic truth.

A brief history of Pluto

1906 Wealthy polymath Percival Lowell speculates on the possibility of “Planet X”, a ninth planet affecting the orbits of Neptune and Uranus. In 1915, his observatory unwittingly photographs Pluto, but the planet remains undiscovered and Lowell dies the following year.

1929 Self-taught junior astronomer Clyde Tombaugh is hired by the Lowell Observatory. He locates Pluto the following year, in roughly the position where Lowell thought “Planet X” should be, by painstakingly comparing numerous photographs of the night sky.

1930 Eleven-year-old Oxford schoolgirl Venetia Burney suggests the new planet be named after Pluto, the elusive Roman god of the underworld. Her father conveys the suggestion to the astronomy community and the name is adopted.

1978 Charon, one of Pluto’s five known moons, is discovered by James Christy of the United States Naval Observatory. The finding allows astronomers to more accurately gauge Pluto’s mass, proving that it is too small to have affected the orbits of other planets. Lowell’s hypothetical “Planet X” is eventually declared non-existent; its proximity to the real Pluto a mere coincidence.

1992 MIT scientists Jane Luu and David Jewitt find conclusive evidence of a dense disc of celestial bodies at the edge of the solar system, now known as the Kuiper belt. Objects of a similar size and mass to Pluto, in a similar vicinity, begin to appear.

2005 A team of Caltech astronomers – led by Mike Brown - discover Eris, a celestial body in the Kuiper belt with a mass greater than Pluto’s. The argument against Pluto’s classification as a planet gathers momentum.

2006 In January, the New Horizons space probe is launched to study Pluto. In August, the International Astronomical Union announces its criteria for “planet” status. Pluto fails to qualify, and is officially demoted to the status of “dwarf planet”. Scientists are divided on the matter - Alan Stern says the agreement “stinks”.

2008 A three-day “Great Planet Debate” is held at Johns Hopkins University to decide on a more satisfactory definition of a planet. The conference reaches no firm conclusion.

2015 New Horizons reaches Pluto after nearly 10 years in space, providing some of the most arresting and detailed photographs ever taken within the solar system.

2016 Mike Brown announces that by using computer modelling he has found evidence for a “Planet Nine”, which has a mass around 10 times that of Earth and an orbit 20 times further from the Sun than Neptune. Kit Buchan

It's like a never ending love story

BalasHapusThat's what makes it worthwhile

Hapus